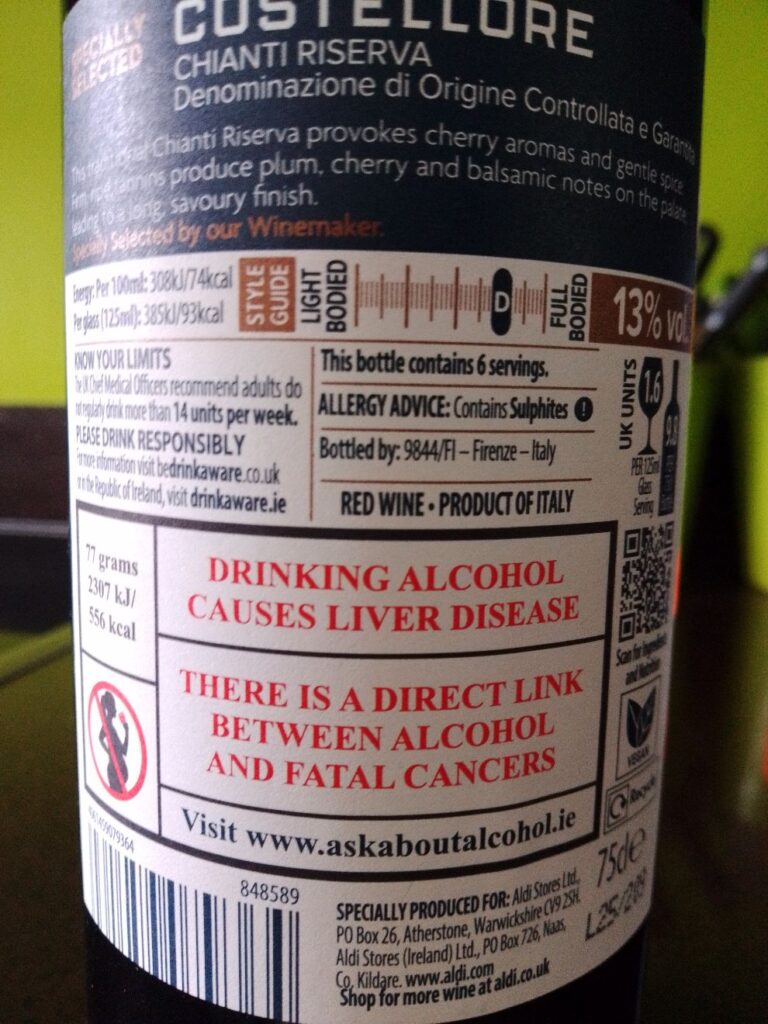

On a recent trip to Aldi I picked up a bottle of wine and did a double-take. The back label carried a stark message that drinking causes liver disease, that there is a direct link between alcohol and fatal cancers. These are the new Irish-style warnings in a UK supermarket, even though this kind of labelling is not mandatory here and in fact is not even fully compulsory in Ireland yet.

Ireland’s labelling rules under the Public Health (Alcohol) (Labelling) Regulations 2023, were signed in May 2023 and were originally due to come into force on 22 May 2026, with a three-year lead-in for industry.

Once they are law, every alcoholic drink sold in Ireland is supposed to carry a standard set of information. Prominent warnings that drinking alcohol causes liver disease, that there is a direct link between alcohol and fatal cancers, plus grams of alcohol, calorie content and a link to an official health website.

The Irish government has now pushed back the moment when these labels become legally compulsory. The original implementation date of 22 May 2026 has been delayed to 3 September 2028. That political decision was taken in mid-2025 and people are framing the delay as a response to uncertainty in the global trading environment and fears about tariffs and trade disputes. Given all that, it would be reasonable to expect that we would only see these labels inside Ireland, and mostly from 2028 onwards. But the reality of supply chains is messier, and that is where Aldi’s shelves come in.

Several producers have decided not to wait. Some began redesigning labels as soon as the 2023 regulations were made, so that new packaging cycles would already comply. Bottles and cans carrying the new warnings are already on sale in Irish pubs and supermarkets, even though the law is not yet fully in force.

Brands such as Kylie Minogue Wines and Graham Norton’s wines have voluntarily added Irish-style warnings and extra health information ahead of the legal deadline. It is simply more efficient to move early rather than run two completely different packaging lines and then scramble to change everything at the last minute.

Labels are often designed and printed long before a vintage hits the shelves and stock can sit in warehouses or on shop racks for a long time. If you know that, at some point in the next few years, Ireland will definitely require those warnings, it makes business sense to standardise sooner rather than later. Otherwise you risk being left with pallets of perfectly good wine that you cannot legally sell in one of your markets.

My Aldi discovery is a case of regulatory spillover. If a producer is selling the same product into Ireland, the UK and elsewhere in Europe, they can either create a special Ireland-only label with the cancer and liver warnings, or they can print one label that works everywhere. One label is cheaper and simpler, so the Irish wording ends up travelling with the bottle, even into countries that have never voted for that particular style of warning.

In the UK at the moment, an Aldi customer might see stark cancer warnings on one bottle and nothing comparable on the next. That patchwork can be confusing. Is one product actually more dangerous or is it just produced by a company that happens to sell a lot into Ireland?

What I am seeing on those Aldi shelves looks like a miniature version of what people sometimes call the “Brussels effect”, where stringent EU rules end up shaping global products because it is easier to comply everywhere than to manufacture separate versions. In this case it is a “Dublin effect”. Rules made for a relatively small domestic market affecting labelling in other countries simply because the same bottles are stocked on both sides of the Irish Sea.