Jean-Noël Kapferer, Emeritus Professor of Marketing at HEC Paris and expert in prestige and luxury management, explores how the concept of luxury applies across different cultures and industries, with particular insight into wine. He defines luxury as something desirable but inaccessible, needlessly expensive, and emotionally powerful. True luxury, he argues, must be “somewhere else”, distinct, exclusive, and difficult to attain.

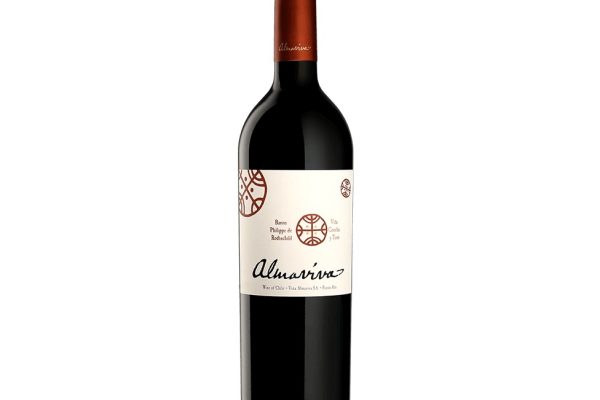

When discussing wine, Kapferer is deliberately provocative, asserting that “there are no luxury wines,” only wines that may form part of a luxurious lifestyle. Even the most expensive bottles remain accessible to the wealthy and therefore cannot reach the same level of unattainability as a yacht or private jet. He observes that no one asks for “a luxury wine” in restaurants, whereas consumers readily use the word “luxury” for cars, watches, or hotels. Instead, wine is more often associated with prestige, a term that carries less exclusivity but more cultural and sensory connotations.

Kapferer notes that genuine luxury requires selective distribution and direct contact with end consumers, something most wine producers lack. Wines and spirits are typically sold through intermediaries such as importers and agents, meaning that control over the customer experience and brand image is limited. In contrast, successful luxury houses like Hermès or Ferrari carefully manage scarcity and customer selection to preserve their aura. He explains that selective distribution should ideally be the final stage before choosing the consumers themselves, as prestige is not only derived from money but from the reputation and status of those who buy and represent the brand.

He acknowledges that some wine producers are attempting to adopt luxury-like strategies, such as restricting access to collectors or private networks as I found at Amarone Calling, but warns that invisibility risks undermining long-term desirability. To remain aspirational, a brand must balance visibility with inaccessibility, desirable but not ubiquitous. Kapferer suggests that prestige wine houses, like other luxury brands, should cultivate this tension to maintain allure while still engaging new generations of consumers.

Ultimately, Kapferer concludes that while wine can embody many of luxury’s values, heritage, craftsmanship, scarcity, and emotion, it falls short of being true luxury because it is still too attainable and too dependent on intermediaries. Its power lies instead in its prestige, its connection to culture, and its ability to accompany and enrich a luxurious way of life.

I am not so sure. In wine, “unattainable” can mean access to an allocation, a cellar, a historic vintage or a vineyard with severe production limits. These barriers can be as exclusionary as money. Equally, the claim that intermediaries prevent luxury overlooks how luxury in many categories is routinely mediated by gatekeepers, from auction houses and private dealers to concierge networks, which can intensify rather than dilute aura. If luxury is emotionally powerful and socially distinctive, then a bottle that is scarce, storied and embedded in a closed world of recognition might function as luxury.