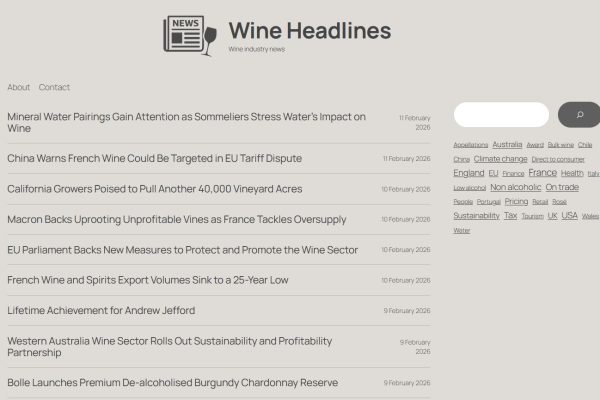

When you purchase a bottle of wine, you might assume that most of the price goes towards the wine itself. However, the reality is often quite different, particularly for lower-priced and very highly priced wines. Here, I explore the complexities of wine pricing and explain why the relationship between price and quality is not as straightforward as it may seem.

In the UK, the pricing structure of inexpensive wines reveals an perhaps unexpected allocation of costs. Consider a £5.99 bottle of wine. Of this amount, £1.00 typically goes to VAT, £2.16 covers UK excise duty, and £0.10 accounts for customs tax. Packaging, including the bottle and label, usually costs around £0.25, while transport adds another £0.40. Retailers, who often have significant margins, take approximately £1.65. This leaves only £0.43 for the actual wine and the producer’s profit a very small proportion of the total price. This breakdown illustrates why many wine experts argue that inexpensive wines provide limited value in the wine itself. However, the reality is more nuanced.

The relationship between price and quality in wine is complex and influenced by numerous factors. Retailers, for example, often negotiate bulk deals with producers, bundling other more expensive wines, enabling them to offer good wines at lower prices without compromising on quality. Some wines are sold as loss leaders where retailers intentionally sell them at a loss to attract customers who might then make other purchases. Overproduction in the wine industry, particularly at the moment, can also lead to surplus stock being sold at discounted prices, allowing consumers to access high-quality wines at lower costs.

Additionally, some producers prioritise high-volume, low-margin production over small-scale artisanal methods. These wines, while affordable, are not necessarily of inferior quality. Conversely, wines from prestigious brands or regions often command higher prices, even when the quality may not justify the premium. Market fluctuations, such as a poor harvest in one region driving demand for wines from another, can also significantly affect pricing. All of these factors mean that a higher price does not always equate to better quality, nor does a lower price necessarily indicate poor value.

The bulk wine market plays a critical role in determining wine prices and availability. It allows producers to sell surplus wine and provides a means for retailers to meet demand during shortages. Prices within this market vary based on factors such as grape variety, region and vintage. This system often enables quality wines to reach consumers at surprisingly affordable prices, further complicating the link between price and quality.

Evaluating a wine’s value, given the complexities of wine pricing, demands a thoughtful and open-minded approach. A great way to minimise bias is have a go at tasting wines without knowing their prices. I’ve experimented with this for myself at various press tastings by not initially looking at the prices. Among upmarket retailers, there tends to be a stronger correlation between price and quality. However, this relationship often breaks down at the lower end of the market and with discount retailers. It’s in these areas that I’ve encountered some of the most striking contradictions. More expensive wines that were frankly disappointing and inexpensive bottles that proved to be superb.

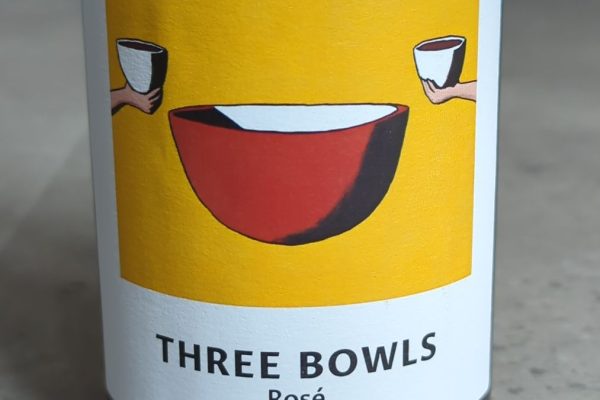

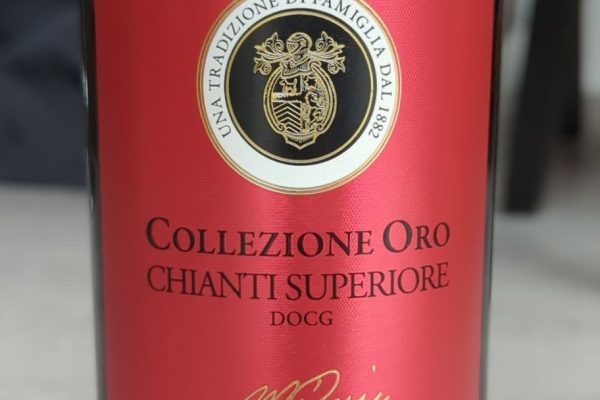

Which ones are inexpensive, you might ask? Take a look at my selection of lower-priced picks. I’ve included some of these, as blind tasted wines, in tastings I’ve hosted and the results have been conclusive. It’s not just me. Many people in the tastings have genuinely thought these wines were worth far more than their actual price, showing that quality and value can sometimes defy expectations.

However, when it comes to higher-priced wines, looking into their production methods can be both enlightening and transformative, prompting a reassessment of what value truly means. Understanding the craft, effort and artistry involved in creating a wine often deepens one’s appreciation, shifting the perspective from viewing value purely in monetary terms to recognising the dedication and expertise that go into every bottle.

It could also be said that the majority of people gravitating towards lower-priced wine can create longer term challenges for smaller, more artisanal producers, those whose work you might want to support and preserve. I believe this is the main motivation behind some wine pundits’ comments when they over-generalise and claim there is no value in less expensive wine. The main question is ‘value to who?’, the end customer, the producer, the future wine ecosystem or indeed the critic?

People also often perceive value in wine through buying brands, much like they do with other consumer products such as smartphones, cars or fashion items. This phenomenon occurs even when the actual differences between wines may be minimal or non-existent. The power of branding in the wine industry plays a significant role in shaping consumer perceptions and influencing purchasing decisions.

A study by Stanford University (Trei, L. 2008, January 16) found the pleasure centres in brains became more active when drinkers thought they were enjoying the more expensive wine. Some consumers derive value from the prestige associated with owning a particular brand, the perception of having purchased the ‘best’ product and the ability to showcase one’s purchasing power or taste to others. I am not criticising this and believe this is legitimate ‘value’.

Despite the strong influence of branding, it’s important to note that the actual quality differences between wines may not always justify significant price disparities. Research has shown that in blind taste tests, even trained tasters often struggle to distinguish between moderately priced wines and their much more expensive counterparts. This suggests that the law of diminishing returns applies as wine prices increase and that much of the perceived value comes from branding rather than intrinsic quality.

Still, at any price point, the ultimate measure of a wine’s worth is personal enjoyment. The best wine will always be the one that resonates with your palate, regardless of how much it costs.

While the price of a wine can provide some indication of its quality, it is never the full story. The interplay of production methods, market dynamics and retail strategies shapes wine prices in ways that often have little to do with the wine itself. By understanding these complexities and focusing on personal preferences, wine lovers can uncover and come to terms with exceptional value at all price points.