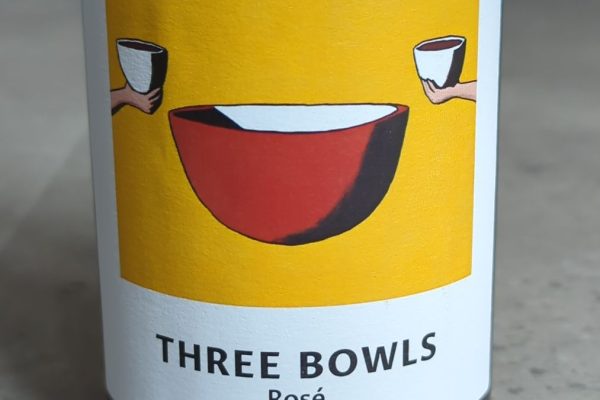

Most wine on the shelf today isn’t made to last. It’s made to taste bright, juicy and ready the moment you get it home. Whites in particular are rarely designed for cellaring. If you’ve bought a simple Pinot Grigio, an unoaked Chardonnay, a typical supermarket Sauvignon Blanc or a fresh rosé, the safest plan is to drink it within months rather than years. Don’t tuck it away for a special occasion. The wine won’t thank you. The fruit will fade, the zest will soften and you’ll be left wondering what all the fuss was about.

That said, some ‘everyday’ styles can age surprisingly well. The trick is understanding what helps a wine hold together over time. Three things act like natural preservatives: acidity, tannin and sugar. Acidity keeps the wine lively and discourages spoilage. Tannin, more relevant in reds, gives structure that mellows slowly. Sugar provides protection against oxidation and allows flavours to deepen. Add good concentration of flavour and, in some cases, a bit of oak or time on lees, and you’ve got a candidate for the short to medium haul.

Riesling is the poster child here. Even modest bottles with decent acidity can improve for several years, shifting from lemon-lime and apple into honeyed, kerosene-tinged complexity. German Kabinett and Spätlese, Aussie Clare and Eden Valley, and Alsace all offer ageworthy examples at sensible prices.

Sauvignon Blanc is trickier. Most Marlborough-style Sauvignons are best young, bursting with gooseberry and passionfruit that dims with time. But there are styles that age nicely. Look to the Loire for Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé with steely acidity and flinty notes, and to Bordeaux whites where Sauvignon is blended with Sémillon and often barrel-fermented; the oak and lees work add texture and the wine develops waxy, nutty tones over five to eight years. South Africa and Chile also produce oak-handled versions that can stretch beyond the usual “drink now” window. So yes, Sauvignon can age, but the label and style matter.

Sweet wines are natural time travellers. Sauternes is a classic example and even half-bottles from modest producers can age gracefully thanks to botrytis concentration, high acidity and sugar. Over time they move from apricot and marmalade to saffron, crème brûlée and toasted nuts. Tokaji from Hungary and German Beerenauslese or Trockenbeerenauslese behave similarly. You don’t need a grand name to see the effect. Even affordable late-harvest or botrytised wines can improve for a decade.

Beyond those, several whites with real acidity and texture can reward patience. Chenin Blanc is superbly versatile: Vouvray from the Loire, or quality South African Chenin, can go from crisp apple to quince, lanolin and beeswax with a few years’ rest. Hunter Valley Semillon looks skinny at bottling, then blooms into lemon curd and toast after five to ten years without ever seeing oak. Muscadet that’s been aged sur lie gains a salty, bready depth and can surprise after three to five years. Alsace Pinot Gris and Gewürztraminer, especially off-dry versions, also fatten into spice and honey.

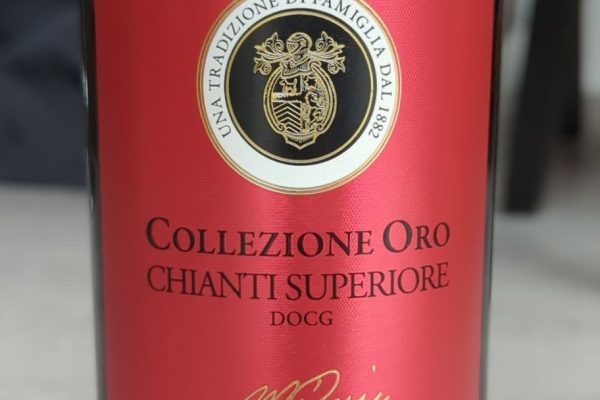

Reds are often more forgiving because tannin adds that extra scaffold. If you like to buy things you can drink now or keep for a little while, look at Côtes du Rhône and Côtes du Rhône Villages, Chianti Classico, Rioja Crianza or Reserva, Douro reds, and Bordeaux Supérieur. These aren’t cellar monsters, but two to six years can soften edges and weave in savoury detail. Malbec from Cahors or Argentina, Syrah/Shiraz from cooler sites, and Portuguese Baga or Dão can also settle into themselves nicely. The theme is the same: decent acidity, moderate tannin, and enough flavour concentration that there’s something to evolve.

Why do these wines age better? Lower pH (which shows up to us as higher acidity) slows chemical reactions and keeps the wine fresh. Phenolics, tannins in reds, and, in some fuller-bodied whites, phenolics from skins and barrels, act as antioxidants, binding up oxygen so it does less harm. Sugar buffers oxidation as well. Time on lees adds compounds that stabilise aromas and texture. Oak, when used thoughtfully, introduces tannin and oxygen in tiny doses, which can make a wine more resilient. Put simply, sturdier building materials make sturdier houses.

A quick word on expectations. “Ages well” for everyday wine usually means “improves or stays the same for a few years” rather than “thrives for decades”. Aim for a realistic window: three to five years for many structured whites and mid-weight reds, longer for sweet wines and certain classic regions. If a label says “sur lie”, “Reserva/Gran Reserva”, “barrel-fermented”, “bâtonnage”, or mentions botrytis or late harvest, your odds improve. If it trumpets “fresh”, “fruity” and low alcohol with no other clues, drink it sooner.

If you do want to keep selected bottles at home, storage matters more than people think. Cool, dark and steady is important. Temperature is the big one: somewhere around 10–14°C is ideal, and, more importantly, stable. Big swings cook wine faster than a consistently warm but steady space. Light is the enemy of delicate aromas, so avoid sunny spots and bright kitchen cupboards. Vibrations aren’t helpful either; wine likes to nap, not commute. A shaded understairs cupboard can be perfectly serviceable. The kitchen is usually the worst room, too warm, too bright, too busy.

Bottles sealed with cork should lie on their sides to keep the cork moist and sealed; screwcaps can stand up, though storing them horizontally won’t hurt. Moderate humidity helps corks, but you don’t need to turn your house into a rainforest; around sixty to seventy per cent is fine. Keep strong smells away, paint, detergents, bin liners, because corks are surprisingly permeable over time. If you’re serious about cellaring but short on space, a small wine fridge is a brilliant upgrade. Even the compact, thermoelectric models hold temperature steady and shield from light.

One practical buying habit: pick up two or three bottles of the same wine. Open one now, store the others, and revisit every six to twelve months. You’ll learn how that style changes in your conditions and can decide if it’s worth buying more to age next time. Also, write the “drink by” goal on a sticky label around the neck.

In summary, most everyday wines are for the here and now, especially whites. They shine soon after release and dim if you hoard them for a big moment. But pick the right styles, zippy, flavoursome whites like Riesling, certain Sauvignon Blancs and oak-handled blends, sweet wines such as Sauternes, and balanced, mid-weight reds with proper acidity, and you can enjoy the gentle magic of time without needing a stately home cellar. Keep them cool, keep them calm, and keep your expectations sensible. Then open and enjoy. That’s what the stuff is for.