The world of wine can be a complex and sometimes intimidating space with countless varieties, regions, and producers, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. This is where wine ratings come into play. They offer a guide to help navigate the vast landscape. However, it’s important to understand wine ratings to know why it’s possible you might not actually like some highly rated wines.

There are essentially two types of wine ratings. The first is a professional evaluation that focuses on the typicity of the wine. The second is personal, which centres on whether an individual or a group of people like the wine. It’s entirely possible to come across wines that are excellent representations of a type or region that you might not personally enjoy. Conversely, there might be wines that you favour that are not typical of a type or region.

When we talk about typicity in the context of wine, we’re referring to how well a wine showcases the characteristics typical of its varietal or region. Take, for example, a Chardonnay from Burgundy. Ideally, it should be light, citrusy and have green apple, lemon, and perhaps hazelnut notes. When a wine critic speaks of typicity, they’re essentially commenting on the wine’s authenticity to its origin, not that they like the wine.

Several factors can influence a wine’s typicity. The terroir, encompassing the soil, climate, and topography of the vineyard, is pivotal. The winemaking process, spanning from fermentation to ageing also moulds the final product. A wine that demonstrates its typicity well is often viewed as a hallmark of quality, reflecting the winemaker’s prowess in retaining the inherent attributes of the grape and its region. For those keen on digging deeper, ‘Defining wine typicity: sensory characterisation and consumer perspectives‘ offers a comprehensive read.

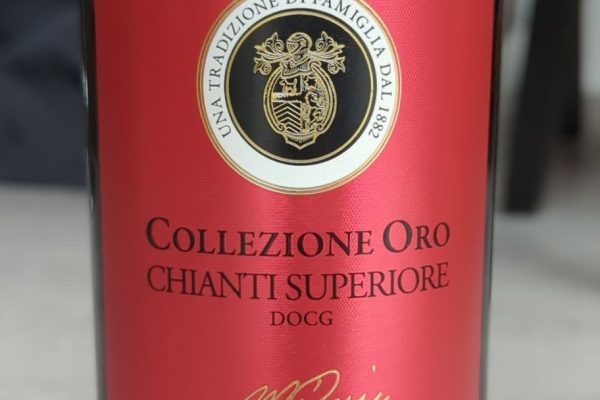

Publications like Decanter, accolades from the International Wine & Spirit Competition, the International Wine Challenge and appraisals by Masters of Wine, primarily focus on typicity. You should rely on these ratings for wines where you already like what’s typical for that type of wine or are eager to discern what a particular wine type should taste like. Decanter has an in-depth explanation of their judging process. In most competitions, scores between 85 and 89 are equivalent to receiving a bronze medal, those between 90 and 94 are akin to a silver medal, and any score above 94 is comparable to a gold medal. However, there has been recent contention over the usefulness of wine scores.

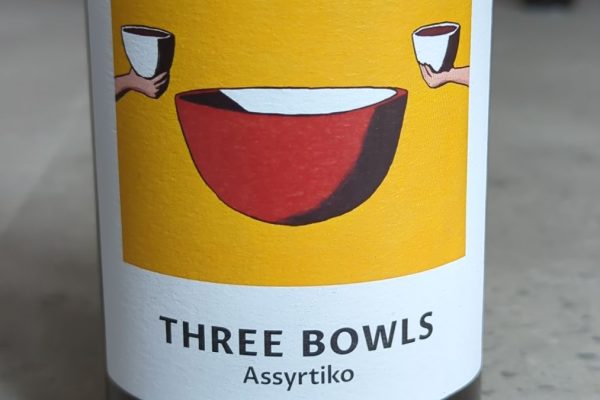

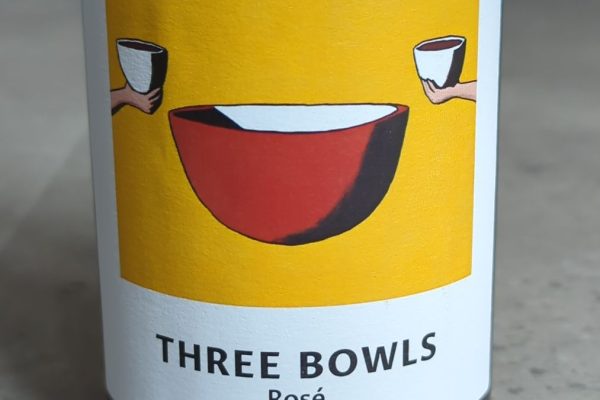

Platforms like Vivino and personal picks such as mine lean heavily on individual taste. A high rating on Vivino is essentially a collective appreciation of a wine’s pleasant taste and not that it is necessarily typical of its type. If you find that you enjoy a few of my picks, it’s likely you’ll appreciate the others as well but, again, they might not be typical of their type.

There are more nuances to this. For instance, judges at Decanter are also prompted to consider the retail value of the wine when scoring, which might influence ratings to some extent. Moreover, our perception of wine is deeply influenced by the context. Factors like mood, accompanying food, weather, the duration for which a bottle has been opened, the wine’s temperature, ambient music and numerous other elements can alter our experience. Additionally, it’s essential to remember that wines are dynamic entities. They evolve over time and attempting to define them at a singular moment might not do them justice.

Considering factors such as these, some people such as Robert Joseph, who boasts over 25 years of experience in various wine competitions, believe that all competitions, and indeed all forms of wine judging, are inherently flawed. Simon J Woolf also asks if wine competitions a load of rubbish.

Finally, in-depth analysis into the pricing of French red wines seems to reveal the significant influence of Vivino ratings, overshadowing the impact of expert evaluations.