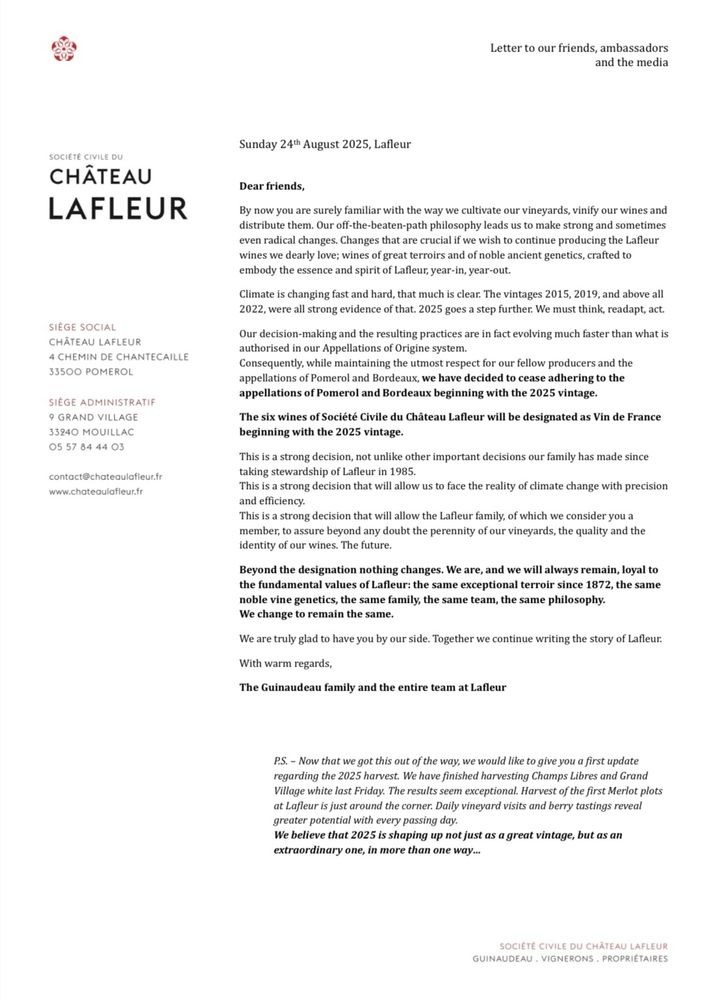

Château Lafleur has fired the starting gun on one of the most consequential shifts in modern Bordeaux. In a letter dated Sunday 24 August 2025, the Guinaudeau family confirmed that, from the 2025 harvest, all six of the estate’s wines will drop the appellations of Pomerol and Bordeaux and be labelled Vin de France. For a domaine whose micro-parcels in Pomerol are among the most coveted in the world, the step is as audacious as it is symbolic.

The letter frames the decision as the logical extension of Lafleur’s long-held philosophy of working “off the beaten path”. It argues that the pace of climate change and the need for nimble, sometimes radical, viticultural choices are outstripping the speed at which appellation rules evolve. The estate stresses that nothing in the vineyards or the cellars will change, only the wording on the label. The same plots, the same genetics, the same team, the same aspiration to express Lafleur’s singular terroir will continue. In the estate’s own words, “We change to remain the same.”

There is also an unmistakable note of urgency. Recent hot, dry vintages have tested the limits of traditional models across Bordeaux, and Lafleur’s letter reads like a manifesto for agility. By stepping outside AOC prescriptions, the family retains full latitude to pick earlier or later, adjust élevage, experiment with plant material and density and take decisions that may be sensible for their parcels but slower to be sanctioned within the rulebook.

France already has a lineage of high-profile refuseniks who have traded appellation for freedom. In Bordeaux itself, Loïc Pasquet’s Liber Pater rejected the Graves classification to pursue pre-phylloxera varieties and ultra-dense plantings. In the Languedoc, the late Laurent Vaillé elevated Grange des Pères to cult status without any appellation seal. In the Jura, Jean-François Ganevat frequently uses Vin de France to bottle eclectic blends, and domaines such as Gramenon in the Rhône and La Grange aux Belles in the Loire have likewise stepped outside their local AOCs after clashes over methodology and style.

Lafleur’s leap, however, lands differently. This is not a maverick outsider or a garage experiment but one of Bordeaux’s most revered addresses, with six immensely sought-after wines. That such a bastion of classical quality has chosen Vin de France sends a message that creative independence and terroir fidelity are not mutually exclusive. It also signals that top domaines now judge the value of flexibility to outweigh the marketing heft of an esteemed appellation name.

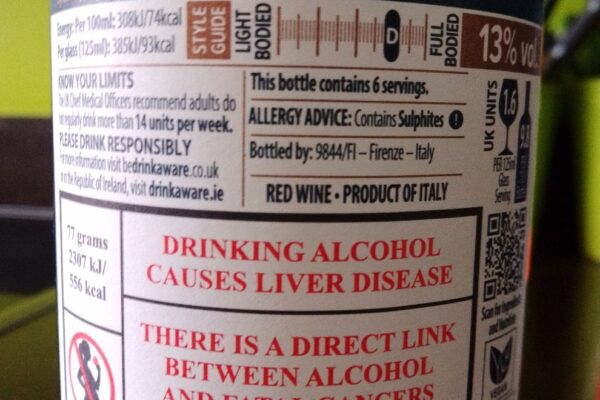

For collectors and trade alike, the practical questions begin now. Pricing will likely detach even further from the old hierarchy of appellations and sit purely on brand, provenance and critical appraisal. Import regulations and market systems, which often hinge on AOC nomenclature, will adapt because demand will force them to. On the shelf and in the cellar, Vin de France may shed the last vestiges of its bargain-basement reputation, completing a quiet transformation into a category that ranges from everyday table wine to some of the most coveted bottles in the country.

What this means for appellations could be profound. If one of Bordeaux’s crown jewels thrives outside the AOC, others may follow, either as permanent exits or as leverage to push for reform. Expect pressure to accelerate approvals of heat-tolerant varieties, to loosen strictures on viticulture and élevage and to create fast-track experimental frameworks that protect origin while allowing adaptation. The power of an appellation has always rested on trust: that the rules help the best sites speak clearly. Lafleur’s move challenges the system to prove that remains true in a warming climate, or risk seeing its most talented ambassadors choose freedom over the imprimatur of place.