Attending lots of supermarket wine tastings, you begin to notice patterns. One of the most notable trends of late is the rise and still growing success of own label wines. These are wines sold under a retailer’s branding rather than that of the original producer. But what’s behind this surge? And what does it mean for producers, retailers and us as consumers?

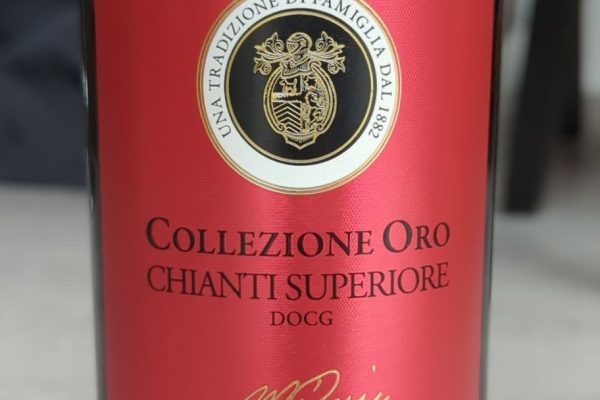

Retailers like Waitrose, Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Morissons and Majestic are upfront about their own label offerings. These wines are proudly integrated into the supermarket’s branding, think Waitrose No. 1 or Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference, and often still reference the original producer. For many everyday shoppers, the supermarket’s brand can carry as much weight as a traditional wine producer’s name, especially among those who are less familiar with the wine world.

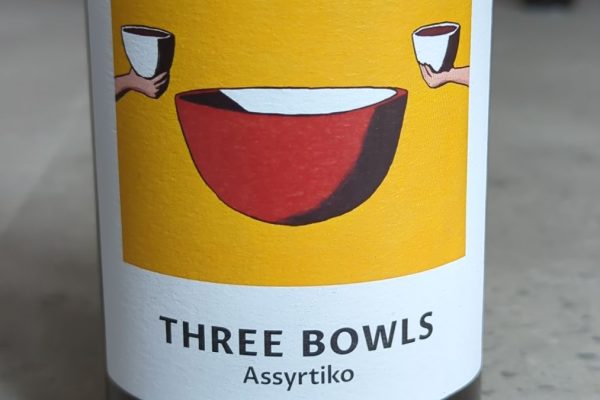

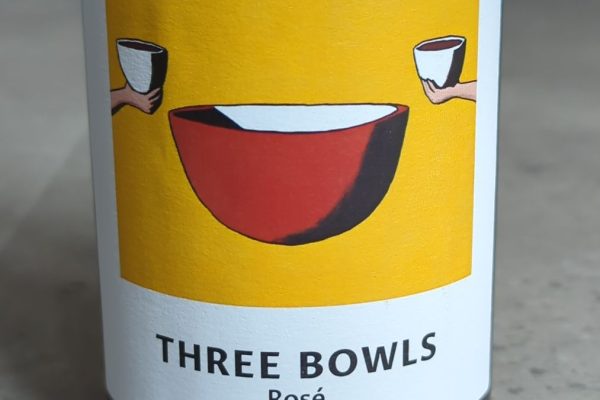

On the other hand, some retailers, notably Aldi and Lidl, frequently employ fictional brand names that look like independent producers. These labels are designed to look like standalone wineries, but the actual producer is often hidden. That said, with a careful look at the back label bottling information and sometimes even the cork, it’s often possible to trace the origin.

Wine producers generally prefer to sell under their own brand, as it brings higher margins and helps build long-term recognition. Creating wines for own label lines can mean managing extra production streams, which adds logistical complexity. So why do it?

One major factor is the current global wine market. Demand has softened, and there’s a surplus of wine. Many producers struggle to sell their own-branded wines in sufficient volume. Collaborating with retailers on own label projects allows them to move stock and access new customer bases that would be difficult to reach independently. These deals often involve higher volumes, which can bring economies of scale, reduce per-bottle costs, and offer more stable revenue through long-term contracts. Additionally, own label projects sometimes allow producers to experiment with grape varieties or techniques without risking their main brand’s reputation.

For retailers, own label wines offer control and profit. By cutting out intermediaries and managing the supply chain more directly, they often enjoy better margins than with traditional branded wines. Retailers can also tailor wines to their specific customer base and set exclusive pricing. Having seemingly unique wines helps supermarkets stand out and encourages customer loyalty.

Of course, it’s not without challenges. Maintaining consistent quality across multiple producers is essential for protecting the retailer’s brand reputation. It can also be hard to position own label wines alongside established brands without seeming ‘budget’, unless the retailer commits to significant own label dominance, which some increasingly seem to be doing. Managing production and bottling logistics with third-party producers is complex too, although bottling wine in the UK after shipping in bulk can streamline operations, reduce costs and can be more sustainable.

So what’s in it for the consumer? Typically, but not always, own label wines offer better value, often coming in cheaper than their branded counterparts. That said, they’re not always budget wines. Many stores ranges now include both entry-level and premium own-label ranges, meaning shoppers have a broad choice of quality and price. Store brands can also be more trusted by casual buyers than unfamiliar producer names and buying a bottle while doing the weekly shop is undeniably convenient.

There are trade-offs, of course. Own label wines can sometimes lack character, prioritising price and accessibility over provenance or uniqueness. Are they as good as independently branded wines from a specialist shop? An older article on Jancis Robinson’s site might suggest not, but the market has evolved. A fair up-to-date comparison might involve the likes of Waitrose No. 1 or the latest Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference range.

Then there’s social perception. Some still prefer to bring a bottle with a known producer’s name to a dinner party rather than one bearing a supermarket badge. And for those who value the independence of producers and shops, there’s a moral tension. Supporting own label wines could be seen as undermining the traditional wine trade, particularly via independent stores. Still, some would argue the overlap between the two markets is limited.

In short, own label wines are here to stay. They’re evolving rapidly, offering surprising quality and value and serving a clear purpose in today’s wine ecosystem. Whether that’s good or bad depends on your perspective, but it’s certainly a trend worth watching.