I recently read a new article at The Drinks Business about how artificial intelligence is being used to change the direct-to-consumer wine experience. It described a Napa Valley winery using AI concierges, conversational commerce and text messaging to increase engagement and sales. While this may sound innovative, to me as someone who works in IT, it feels like a narrow view of what AI could offer and one that mainly serves the winery rather than the drinker.

The approach described is simplistic because it relies on chat tools that are limited to a single producer’s range and perspective. In practice, this is little more than a branded information service. Many people do not actually want to talk to customer support chatbots and still prefer human advice when it is available. In reality, these tools often exist to replace staff or to provide guidance where employing knowledgeable people is no longer affordable, which reflects the financial pressure across much of the wine trade. In that sense, the benefits flow primarily to the seller, potentially at the expense of the consumer if human interaction has actually been removed.

The more important question is whose interests the AI is designed to serve. If it is funded by wine sales, it is reasonable to assume that it may quietly favour options that suit the seller, even if this is not obvious to the user. That tension will become central as AI becomes more capable.

Looking more broadly, AI is already moving beyond basic chat interfaces towards ‘agent’ systems that can plan, evaluate outcomes and search for information in order to achieve a goal. Early so called ‘thinking’ versions of AI already exist and are available. This opens up far more interesting possibilities if the starting point is the consumer rather than the brand.

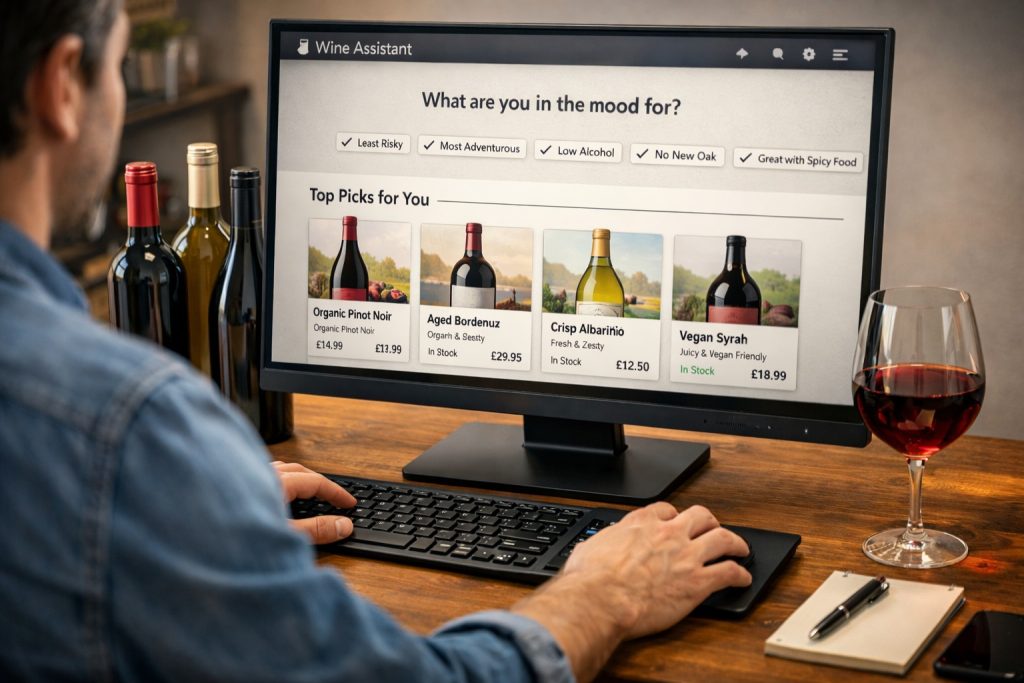

A consumer-first model would be open about any commercial relationships, show genuine alternatives at different price points, and explain the compromises involved in each choice. It would allow people to set their own priorities, such as minimising risk, trying something unfamiliar, choosing lower-alcohol wines, avoiding new oak, or finding bottles that work well with spicy food, without being pushed towards a particular sale.

From the drinker’s point of view, the real opportunity lies in having a ‘persistent’, always-there, AI assistant that works on their behalf. Instead of juggling multiple retailers, apps and websites, this kind of system could plan, search, track and coordinate across many sellers. Unlike today’s recommendation engines, it would not stop at suggestions but could carry tasks through from start to finish, within rules set by the user, and learn from feedback such as what you enjoyed, what felt too oaky, what worked with a particular meal, or what was not worth the money.

One of the clearest uses is shopping across multiple merchants in a way that genuinely reflects personal preferences. An AI assistant could hold details about your tastes, spending limits, alcohol preferences and requirements such as organic or vegan production, low sulphur claims, or an avoidance of heavy oak. It could then search across sellers for wines that are actually available and deliverable to your postcode, deal with comparisons between vintages, delivery charges, mixed cases and discounts, and present a short list with clear explanations of the differences. Over time, it could respond to requests like finding an everyday red under £15 that is not overly sweet, rather than defaulting to broad regional labels.

Beyond shopping, there is value in managing continuity. If a regular purchase becomes unavailable or suddenly increases in price, an assistant could suggest close alternatives, explain what would stay similar and what would change, and keep track so you are not repeatedly hitting the same dead end. This removes a lot of low-level frustration from buying wine regularly.

Another step is acting as a personal cellar and drinking-window manager across all purchases, not just those from one shop. By consolidating orders from different merchants, an AI could track what you have, estimate when bottles are best opened, and offer timely reminders. If you are hosting, it could suggest what to chill, when to open things, and how to sequence drinks for guests, including non-alcoholic options if needed.

Meal planning and pairing also benefits from this wider view. Given a week’s worth of meals, an assistant could suggest a small selection of bottles sourced from different sellers that covers the range, avoids repetition and respects your preferences. For difficult dishes, such as those involving artichokes, chilli heat or sharp sauces, it could help steer you away from styles that are likely to clash and towards more forgiving choices.

Tracking value and pricing is another area where consumers could gain confidence. An assistant could monitor prices on wines you enjoy, flag meaningful discounts, and help avoid paying inflated prices driven by hype. It could also reflect your own definition of value, such as favouring freshness and acidity in whites or restraint in reds, rather than external scores. At a more advanced level, it could help manage a monthly spend, balancing everyday bottles with occasional treats.

For learning, this kind of system could act as a private tutor grounded in what you actually drink. After a quick note or label scan, it could ask a small number of useful follow-up questions and link your impressions to specific characteristics, suggesting what to try next to refine your understanding of your own tastes.

Finally, there are social and gifting uses that cut across retailers. An assistant could remember, or link to, what friends or family tend to like, keep a list of reliable gift options at different prices, manage delivery timing and avoid repetition. For events, it could estimate quantities, suggest a balanced selection and source it efficiently from available merchants.

The challenge in making this work is coordination across sellers. From my experience working with offers, it is clear that some retailers’ data is difficult to access or standardise. This may improve as businesses recognise that making information more accessible helps AI systems surface their products more effectively. In the near term, this is likely to appear as partly automated assistants that can browse, compare and prepare baskets but still ask for approval before purchase, often using emails and receipts to bring order histories together. As these foundations improve, more fully integrated experiences might become possible.