Bulgaria encompasses six thousand years of winemaking tradition, now blending ancient heritage with modern innovation. It cultivates both native varieties and international grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay.

With over 90% of production exported to markets across Europe, Asia and North America, Bulgaria’s is experiencing a resurgence as a competitive force in the global wine industry.

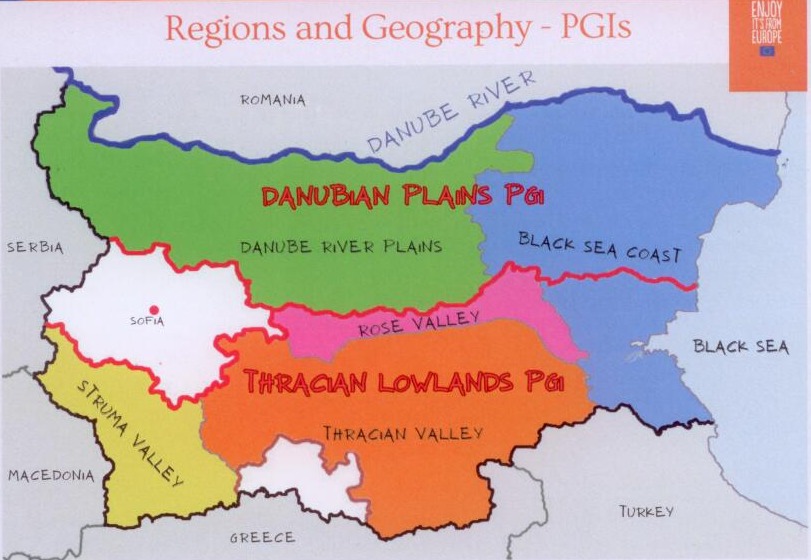

Bulgaria’s Wine Regions and the PGI Framework

Bulgaria’s wine regulatory landscape transformed significantly upon joining the European Union in 2007, adopting the EU’s Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) and Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) frameworks. The country now recognises two expansive PGIs, Thracian Lowlands and Danubian Plains, which together account for 60–65% of national production. While PGIs enforce looser regulations on grape varieties and yields, Bulgaria’s 52 PDOs impose stricter standards akin to France’s AOP system, though only a handful are actively used.

Critics argue that the PGI zones’ vastness, spanning hundreds of kilometres, dilutes regional distinctiveness. For instance, the Thracian Lowlands PGI stretches from the Struma Valley near Macedonia to the Black Sea coast, encompassing dramatically varied terroirs and over 60,000 hectares. Some producers like this as it allows them to source grapes from neighbouring areas. However, others prefer Bulgaria’s pre-EU regional divisions: the Thracian Valley, Danube River Plains, Black Sea Coast, Rose Valley and Struma Valley. These smaller zones better reflect microclimatic nuances, yet the PGIs remain crucial for export certification and international branding. There are moves to try to get the smaller zones recognised as PGIs.

From Bulgarian Tasting

Dionysus and the Birth of European Winemaking

Archaeological evidence confirms that Thracian tribes inhabiting modern-day Bulgaria produced wine as early as 4000 BCE, predating Greek and Roman viticulture. The Thracians revered wine as a sacred conduit to the divine, with Dionysus, originally the Thracian god Zagreus, central to their rituals. Unlike the Greeks, who diluted wine with water, Thracians consumed it undiluted, a practice that astonished classical historians.

Thracian wine culture flourished through intricate golden vessels like the Panagyurishte and Valchitran treasures, designed for ceremonial libations. Homer’s Iliad even references Thracian wines as prized by Trojan elites, underscoring their ancient renown. Despite Ottoman prohibitions on alcohol production from 1396 to 1878, clandestine vineyards preserved indigenous varieties like Mavrud and Pamid, ensuring continuity into the modern era.

Terroir and Viticultural Profile

The Thracian Lowlands’ continental climate features hot summers, averaging 28°C, mild winters, and annual rainfall of 550–650 mm, moderated by the Balkan Mountains’ rain-shadow effect in western zones. The region’s latitude parallels southern France and central Italy, offering comparable growing seasons. Soil diversity, from fertile chernozems to limestone-rich cinnamonic types, supports varied styles:

- Western Subregions (Asenovgrad, Perushtitsa): Sheltered valleys with well-drained slopes ideal for structured reds.

- Central Zones (Stara Zagora, Korten): Alluvial plains yielding high-volume fruit-forward wines.

- Eastern Areas (Black Sea proximity): Maritime influences foster crisp whites and sparkling wines.

The Danubian Plain is situated in northern Bulgaria along the southern banks of the Danube River. The region experiences a temperate continental climate, marked by hot summers, cold winters and dry autumns. Annual precipitation typically ranges between 450 and 650 mm. The Danube River plays a crucial role in moderating temperatures, creating favourable conditions for viticulture. The soils in the area are diverse, predominantly fertile and dark, with loamy and granular textures that allow for good permeability. Additionally, alluvial soils influenced by the Danube further enhance the fertility of the land. Vineyards are often situated on gentle slopes near mountain valleys, benefiting from optimal sun exposure and effective drainage, making the region well-suited for high-quality wine production.

Indigenous Varieties

Red Misket, also known as Misket Cherven, is an ancient Bulgarian grape variety with pinkish-red to violet skin, primarily used for white wine production. It thrives in the Rose Valley and Sungurlare regions, particularly on alluvial and limestone-clay soils. The grapes are juicy and sweet, with a distinct floral “misket” aroma. Wines produced from Red Misket are of high quality, typically displaying pale greenish or golden hues. The aroma profile includes floral notes, yellow fruits, rose, vanilla and tropical fruits. The wines are light-bodied with a refreshing aftertaste and a noticeable minerality. Red Misket is often blended with Riesling or Dimyat to enhance complexity.

Sandanski Misket is a modern cross between the red Broad-leaved Melnik grape and the white Tamianka grape. It is primarily cultivated in the Struma Valley. This variety is highly aromatic, offering flavours of mandarin, grapefruit, yellow flowers, peach and acacia. The resulting wines are crisp, refreshing and perfumed with mineral notes. Although plantings of Sandanski Misket remain relatively small, there is increasing interest in this indigenous variety. The wines typically have a pale lemon hue with pink hints. Their balanced acidity and oily texture make them well-suited for pairing with seafood and salads.

Vrachanski Misket, also known as Vratsa Muscat, is an old Bulgarian white grape variety grown predominantly in northwestern Bulgaria. It flourishes on hills with southern exposure and prefers humus-carbonate or clay-sandy soils. The grapes have thick skins and succulent pulp, producing a muscat flavour. This variety is resistant to rot but sensitive to drought and low temperatures. Wines made from Vrachanski Misket are typically dry, with greenish-yellow hues and aromas of orange peel, tangerine and grapefruit. They exhibit fresh acidity, a harmonious taste, and a long-lasting finish, making them elegant and persistent.

Tamyanka, also known as Tamjanika or Temjanika, is a variety of Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains, one of the oldest and most aromatic Muscat grapes. It is also cultivated in Serbia and North Macedonia, with its name derived from “tamjan,” meaning frankincense, due to its intense fragrance. The grape is highly aromatic, offering notes of lime, lychee, exotic fruits, flowers and spices such as cloves and ginger. It ripens between early and mid-September. Wines made from Tamyanka range from dry to semi-dry and sweet, having a fresh, elegant, and refined muscat-like profile. The best expressions of this grape come from vineyards in northern Bulgaria along the Danube Plain or southern regions with significant diurnal temperature variations. It is often blended with Chardonnay but is also produced as a single-varietal wine.

Dimyat is an ancient Bulgarian white grape variety with possible Thracian origins. It is widely grown in eastern Bulgaria and along the Black Sea coast. The grape produces large clusters of juicy berries with a golden-yellow colour. While it is a high-yielding variety, it is also sensitive to diseases and frost. Dimyat has a neutral flavour profile with moderate acidity and sugar content. It is commonly used for white table wines, brandy production and blending. Wines made from Dimyat are typically light-bodied, with delicate floral and fruity aromas, including apple and pear. Due to its freshness, it is also suitable for sparkling wine production. The Thracian Valley and Black Sea regions are particularly well known for growing this variety.

Keratsuda is a rare indigenous Bulgarian white grape variety originating from the Struma Valley in southwestern Bulgaria. Its name means “girl” in Greek. The grape produces small to medium-sized berries that ripen late in the season. It has an aromatic profile featuring notes of pear, apricot, white flowers and honey. While Keratsuda is resistant to drought, it requires careful cultivation due to its low yields. The wines produced from this variety are often light white wines or orange wines made with skin contact. They typically exhibit a dark gold to amber colour with robust flavours and a pronounced minerality. Known for its elegance, Keratsuda has the potential to produce complex wines that age well.

Rubin is a hybrid grape variety developed in Bulgaria in 1944 by crossing Nebbiolo from Italy and Syrah from France. It is primarily cultivated in warmer regions such as the Thracian Valley, where it thrives in the favourable climate. The grapes are medium-sized, dark blue, and have thick skins, which contribute to the wine’s rich colour and structure. Wines made from Rubin are full-bodied with an intense ruby hue, offering aromas of blackberries, cherries, plums, and spices. The wines are known for their velvety texture, balanced acidity, and high tannins, making them well-suited for aging.

Pamid is an ancient Bulgarian grape variety with Thracian origins. It produces large clusters of thin-skinned, light red berries and is primarily grown in warm climates. However, it is sensitive to diseases, which has contributed to its decline in popularity. Pamid is a low-tannin, low-acidity variety, making it suitable for fresh consumption as well as for producing light-bodied red wines. These wines have pale ruby hues and delicate aromas of red berries and herbs. Historically, Pamid was widely planted, but due to its limited complexity, it has been largely replaced by more structured varieties.

Gamza, also known as Kadarka in other Balkan countries, is an ancient grape variety long associated with Bulgaria, particularly in the northern Danubian Plains. It produces thin-skinned grapes that ripen late and are prone to mould in humid conditions. Wines made from Gamza are typically light to medium-bodied, with bright aromas of cherries, raspberries and cranberries. They have soft tannins and fresh acidity, often drawing comparisons to Pinot Noir or Gamay. Gamza wines are best enjoyed young, as they highlight the grape’s fruity vibrancy and freshness.

Melnik is an indigenous grape variety from southwestern Bulgaria, specifically the Struma Valley, named after the town of Melnik. It includes different sub-varieties, with Broad-leaved Melnik Vine being the traditional form and Melnik 55 being a hybrid bred for earlier ripening. The grapes are small with thick skins and require warm climates to fully mature. Wines made from Melnik grapes are full-bodied with robust tannins and moderate acidity. They are known for their distinctive aromas of dried herbs, tobacco, cherries and spices. These wines age well, developing complex earthy and smoky notes over time.

Mavrud is one of Bulgaria’s most celebrated indigenous grape varieties, with a history dating back to ancient times. Its name comes from the Greek word “mavro,” meaning black, reflecting the deep colour of its wines. Mavrud is a late-ripening variety that requires warm climates, such as the Thracian Valley, to reach full maturity. The grapes have thick skins, resulting in wines with high tannins and acidity. Mavrud wines are deep ruby-red, featuring flavours of blackberries, cherries, prunes and chocolate. They are full-bodied and possess excellent aging potential. When aged in oak, the wines develop additional complexity with notes of cedar and smoke.

Export

Bulgarian wine exports surged by 22% between 2020 and 2024, with the Thracian Lowlands contributing €85 million annually. Key markets include:

- EU Nations: Poland, Germany and the UK favour budget-friendly Cabernets and Merlots.

- Asia: Chinese consumers prize Mavrud as a boutique curiosity, while Japan imports sparkling wines.

- North America: Niche demand for organic-certified blends and heritage varieties.

Conclusion

Bulgaria’s wine renaissance honours its legacy as Dionysus’ birthplace while embracing contemporary techniques. Challenges persist, notably in branding distinctiveness of international varietals against global competitors, yet the region’s diverse offerings position it for renewed acclaim. As EU funding bolsters sustainable practices and tourism infrastructure, Bulgaria could reclaim its ancient status as a cornerstone of Old World viticulture.