At a high level, what you taste in a wine comes from three places: the grapes and their fermentation (primary aromas and flavours), the choices made after fermentation (secondary, such as oak, malolactic and lees) and the effects of maturation and age (tertiary). Thinking in these three layers helps you separate where specific notes and textures originate.

The growing environment is fundamental because it governs how grapes ripen, which sets the baseline for sugar, acidity, tannin, alcohol and the spectrum of fruit and non-fruit flavours. Vines need heat, sunlight, water, nutrients and carbon dioxide to complete their annual cycle and variations in these shift both the quantity and the flavour quality of the crop. For instance, grape sugars rise and acids fall during ripening; if conditions are too cool or the season too short, flavour development lags, whereas adequate warmth and light drive photosynthesis and ripening. Not all varieties need the same heat, Riesling can thrive in cooler sites that would leave Grenache under-ripe, so grape and site must match if you want balanced flavours.

Climate and temperature patterns shape style and taste in recognisable ways. In cool to moderate continental climates, short summers and spring frost risk push growers toward earlier-ripening varieties and can yield lighter wines with higher acidity; in maritime climates, long, mild autumns can fully ripen thicker-skinned grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon but rainfall can dilute flavours or disrupt flowering; in Mediterranean settings, extra warmth and sun typically give fuller-bodied wines with riper tannins, higher alcohol and lower acidity. Diurnal range and continentality matter too: cooler nights help preserve aroma and acidity, while wide seasonal swings change what will ripen reliably. All of these factors feed directly into what you perceive in the glass.

Sunlight and water each push flavour in different directions. More light means more photosynthesis, better flowering and riper flavours, but excessive sun can scorch skins and create bitter notes; aspect and slope are used in cool zones to maximise sun exposure. Water drives photosynthesis and berry swelling; after the canopy is established, mild water stress re-focuses the vine from vegetative growth to fruit ripening, concentrating flavour, whereas drought halts ripening and excess water swells berries, diluting flavour.

Soils don’t flavour wine directly, but they control water and nutrient supply and therefore ripening and balance. Clay and humus hold water; sandy, stony soils drain freely; too much clay risks waterlogging and vine stress, while very sandy profiles may force irrigation. These differences affect berry size and ripening rate, which you perceive as changes in concentration, freshness and texture.

Vineyard management refines these raw ingredients. Canopy decisions aim to admit light and air while avoiding sunburn or shading; in cool, rainy seasons a vertical shoot-positioned canopy helps maximise light and reduce fungal disease, preserving fruit purity. Bud numbers and planting density influence vigour and the evenness of ripening; if yields are excessive, flavours can be dilute, though the book cautions that the link between yield and quality depends on site and timing. Harvest timing fixes the final balance: sugars rise, acids drop, skins and tannins soften, and varietal flavours move from herbaceous to ripe to over-ripe; picking too early or too late is immediately obvious in the taste. Disease pressure matters as well, as some infections strip fruit character and impart mouldy, bitter taints.

Winemaking choices then shape flavour, aroma and texture. In white wines, brief skin contact on aromatic varieties can boost flavour intensity and texture; clarifying the juice avoids off-aromas; cooler ferments emphasise fresh, fruity characters, whereas warmer ferments bring more complex, non-fruit notes. Fermentation vessel matters: stainless steel protects fresh fruit; barrels add subtle oxidation and oak-derived flavours, encouraging complexity. After fermentation, decisions about oak ageing, lees contact and whether to allow or block malolactic fermentation (MLF) alter both taste and feel: lees contact and stirring add creamier texture and savoury, bready notes; MLF softens sharp acidity and introduces buttery tones, which can be welcome in some styles and undesirable in others.

Red winemaking adds another layer because colour, flavour and tannin are extracted from skins during fermentation. Temperature control and cap management techniques (punch-downs, pump-overs, rack-and-return, rotary fermenters) determine how much and which tannins and pigments you extract; over-extraction can leave wines tasting bitter and astringent, while gentle handling preserves juicier fruit. Post-fermentation maceration can further soften or build structure, and oak choices during maturation contribute spice, toast and structure at levels the fruit can support.

Ageing transforms flavour again. Oxidative ageing, often in oak, tends to move wines towards coffee, toffee and caramel notes; protected ageing in bottle brings petrol, honey or mushroom in whites and leather, forest floor and tobacco in reds. As wines age, primary fruit becomes less fresh and can turn dried or cooked; when well-judged this adds complexity, but push it too far and wines become tired.

Blending is a final lever to tune taste. Combining varieties, press fractions or lots raised in different vessels can balance colour, body, tannin, acidity and flavour, or weave in more or less oak character for harmony.

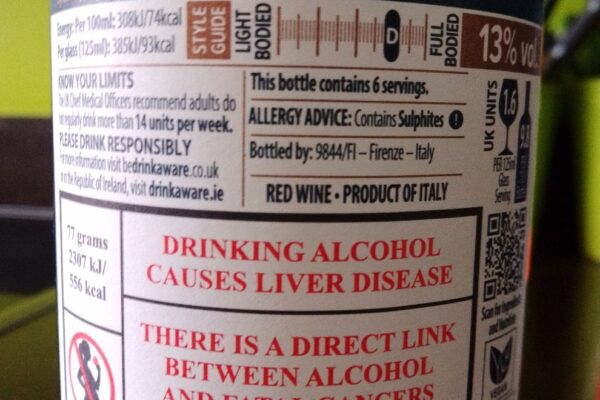

Lastly, faults and storage conditions change taste in obvious ways. Oxidation deepens colour and mutes fruit, bringing toffee or coffee notes; volatile acidity adds vinegar or nail-polish impressions; Brettanomyces can layer in leathery, meaty or plastic notes that some tolerate and others dislike; poor storage leaves wines out of condition, dulling freshness. These are not “style” choices but they are part of what you can taste.

In short, taste is built first in the vineyard by climate, site and farming, then sculpted in the winery by fermentation, extraction and maturation and finally evolved by time in barrel or bottle. Understanding which of these levers has been pulled, and how far, explains why a wine tastes the way it does.