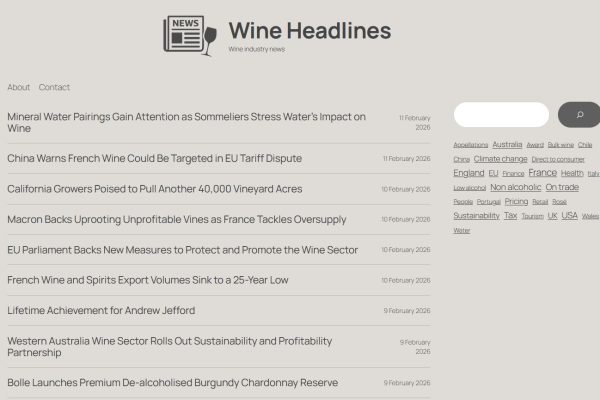

Mike Veseth has a thought-provoking article on Theories of the Global Wine Glut. The world seems to be overflowing with surplus wine. In Australia, there’s an estimation that suggests that the surplus could fill 859 Olympic-size swimming pools which translates to roughly 2.8 billion bottles. In France, the government has set aside two hundred million euros for crisis distillation. This means surplus wine will be purchased to maintain local prices and then distilled into industrial alcohol.

While wine surplus isn’t a new phenomenon, the current situation seems different. Historically, wine, being an agricultural product, has seen periodic booms and busts. However, the present surplus appears more permanent. One reason for this is the global nature of the surplus, which is driven more by insufficient demand than by excess supply. Wine consumption had been rising steadily for two decades until the global financial crisis around 2007/8. This growth halted during the financial crisis and further declined during the COVID-19 pandemic. Post-pandemic, the consumption hasn’t bounced back, with levels resembling those of the early 2000s.

To understand the global wine glut, Mike Veseth presents some theories:

The Generation Gap Hypothesis: This theory suggests that while the Baby Boom generation significantly contributed to the rise in wine consumption, subsequent generations haven’t shown the same enthusiasm. The challenge is to introduce younger audiences to wine, possibly through marketing or cultural education programs.

The Life Cycle Hypothesis: This theory suggests that all generations have a latent demand for wine, which only manifests at a certain life stage. Millennials are just now reaching this stage. However, since post-Boomer generations are numerically smaller, even if they develop a taste for wine, their numbers won’t be sufficient to match the consumption levels of the Baby Boomers.

Digging deeper, why is there a generation gap? Among the younger generation, there’s a noticeable trend of either reducing alcohol intake or abstaining altogether. A study by BMC Public Health looked into the reasons behind the decline in youth alcohol consumption in England over the past two decades. This research, which took the perspective of the youth, pointed to several reasons: heightened awareness of the health risks associated with alcohol, changes in youth socialisation patterns due to the prevalence of social media, economic factors making alcohol less affordable, a preference for other substances over alcohol and legislative measures that restrict access to places selling alcohol.

Studies show that as Gen Z individuals transition into adulthood, they’re adopting a more cautious approach. Many either don’t drink at all or consume alcohol less frequently and in smaller quantities than the preceding generations. In 2019, a major study on drinking behaviours in the UK revealed that 16-to-25-year-olds were the group most likely to abstain from alcohol, with 26% identifying as teetotal. This contrasts with the 55-to-74-year-old age group, where only 15% abstained.

This is a global phenomenon. In the US, a Gallup poll indicated that 70% of those aged 35 to 54 consume alcohol, compared to 60% of Gen Zers and 52% of Boomers. Furthermore, a 2020 study highlighted that the percentage of teetotal college-aged Americans has increased from 20% to 28% over ten years.