From 1 February 2025, the UK implements new alcohol duty rates, ushering in changes that will significantly impact both importers and consumers. With 30 different duty rates to navigate, the complexity of this system is daunting, particularly for importers. For consumers, the effects will be felt primarily in pricing and in some cases a change to wines.

The first factor driving this change is the adjustment of alcohol duty rates in line with the Retail Price Index (RPI) inflation. On top of this, wines will be subject to a new sliding scale of duty meaning the higher the alcohol content, the greater the duty. From talking to producers and importers at tastings, I know the new duty rates and global health concerns have prompted many importers to encourage their producers to lower the alcohol levels of their wines, raising the question, what will this mean for the wine market?

The effects of these changes are expected to be most noticeable in the low- to mid-priced wine segment, particularly wines priced say under £15. For higher-priced wines, the fixed cost of duty is proportionally small, meaning their pricing may be very much less sensitive to these changes. However, for more competitively priced options, every penny counts. Many wines will see price increases between £0.30 and £0.60 per bottle but with additional issues could push some bottles up by £1 by next year. Beyond the duty itself, other factors are contributing to rising costs, including new importer systems to manage the duty complexity. For example The Wine Society expect this to cost around £3 million next year which has caused them to freeze recruitment and cancel investment plans. Add to this the Extended Producer Responsibility packaging scheme and recent national insurance increases and it becomes clear why many importers will need to pass these costs onto consumers.

The sliding duty scale has encouraged some importers to press producers to aim for 12.5% or below to keep the sliding scale part of duty similar or less than previously. This is particularly pertinent for red wines, as most white wines already fall below this threshold. But lowering alcohol content is not without challenges. Producers can adjust vineyard practices by decreasing sugar levels in grapes, achieved through canopy leaf removal or other vineyard techniques. They can use nanofiltration to remove sugar from the must prior to fermentation or rely on lower-yield yeast strains designed to convert less sugar to alcohol. Post-fermentation alcohol removal can also be employed through methods such as reverse osmosis, vacuum distillation or spinning cone columns. While these techniques are effective, they come at a cost. They also risk altering the wine’s flavour, a compromise many producers are unwilling to make.

The legalisation of in-market ABV adjustments following post-Brexit wine reform in 2024 could also benefit bulk wine, enabling producers to reduce costs by lowering alcohol levels after it has been received in the UK. Sophisticated de-alcoholisation technology in the UK allows precise ABV reductions, avoiding the need for expensive, complex processes in overseas wineries. This flexibility can help producers manage duties incrementally, reducing costs by approximately £0.11 per 0.5% ABV decrease. The technology also ensures consistency across vintages.

This shift to accommodate the UK market could have broader consequences. The UK is already a challenging market, financially and Brexit-wise, for many producers and these additional costs and requirements could push more, especially smaller or financially strained vineyards, to cease supplying to the UK altogether. This could reduce consumer choice.

As these changes take effect, consumers and importers will need to adapt. For consumers, this likely means paying more for their favourite wines or exploring options with lower ABV. Importers face the dual challenge of navigating the complexity of the new system while balancing costs and maintaining relationships with producers and their business customers. While a global trend towards lower alcohol consumption may provide some alignment, it’s clear that the new UK duty regime adds a layer of difficulty and could reshape the wine market. Whether this leads to innovation or a contraction in supply remains to be seen as it will take months inventories to be replaced. For now, wine lovers should prepare for a more expensive and potentially a changed or narrower range of options.

The price of wines is expected to increase gradually due to the way taxation is applied at the point of import rather than point of retail sale. Importers currently hold existing stocks, which means that immediate price hikes won’t be seen across all wines. However, as new shipments arrive, individual wines will experience price increases in line with rising import duty costs. A few retailers might choose to adjust all their prices pre-emptively, anticipating the inevitable rise in replacement costs, but its unlikely as they will wish to remain competitive. This means consumers can expect a steady upward trend in wine prices over time.

One more thing. All this might make you consider stocking up on wine to avoid future price increases. I used to think this way myself, but I’ve since changed my approach. The reality is that the majority of wine evolves over time and not always for the better. Apart from the very small percentage of wines specifically made to improve with age, most bottles are meant to be enjoyed relatively young. Stocking up for the long term, say, beyond six months, might save on costs initially, but by the time you get around to drinking those bottles, they may not taste as intended. For me, it’s not worth the risk of trading savings for the potential compromise in quality.

Updates:

Daniel Lambert has criticised HMRC’s new wine excise laws, which he believes are deeply flawed and prone to exploitation. He argues that the policy’s reliance on wine labels and invoices for alcohol by volume (ABV) declarations is inadequate, as labels often provide only approximate ABV values and invoices can be manipulated. With no regulatory checks in place, especially on international producers, he warns that many will understate ABVs to reduce tax, leading to widespread fraud, reduced government revenue, higher prices and limited choice for consumers. He highlights that HMRC expects precise ABV declarations, yet offers no reliable framework to achieve this. Additionally, inconsistencies between DEFRA and Treasury definitions exacerbate the confusion. Lambert contends the policy misunderstands the unique nature of wine, as its ABV naturally varies, unlike beer or spirits, making the rules unfit for purpose. He attributes the policy’s failure to inadequate scrutiny by both the Conservative and Labour parties and a lack of understanding by policymakers.

I found this on the Majestic web site which is a great visualisation of the increased costs and uncertainty of pricing as ABV changes over time:

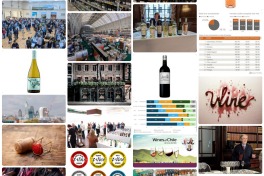

Found this interesting table by the AAWE that shows that Finland, Ireland and the UK impose the highest taxes, by far, on still wine: