A hidden part of the UK wine industry to consumers, is the process of bulk packaging, transporting and local UK bottling of wine which represents about 40% of imported wine. This reduces transportation costs and the environmental impact but also carries implications for the provenance and authenticity of the wine.

If you look at the back label of a bottle you might see a bottling code rather than a statement that it’s bottled near origin.

The bottling plant code on wine bottles is typically, F for France, D for Germany, and W, commonly used for the UK. While the use of these codes enhances transparency regarding the bottling origin, they sometimes stir discussions about the loss of authenticity. Particularly for more expensive wines, consumers might expect the original bottle from the source. Such concerns have been raised, for example, among members of The Wine Society seeking clarity on bottling provenance.

Major supermarkets like Tesco and ASDA, alongside drinks giant Accolade, operate their own bottling plants. In addition, independent companies like Greencroft Bottling are part of this supply chain process.

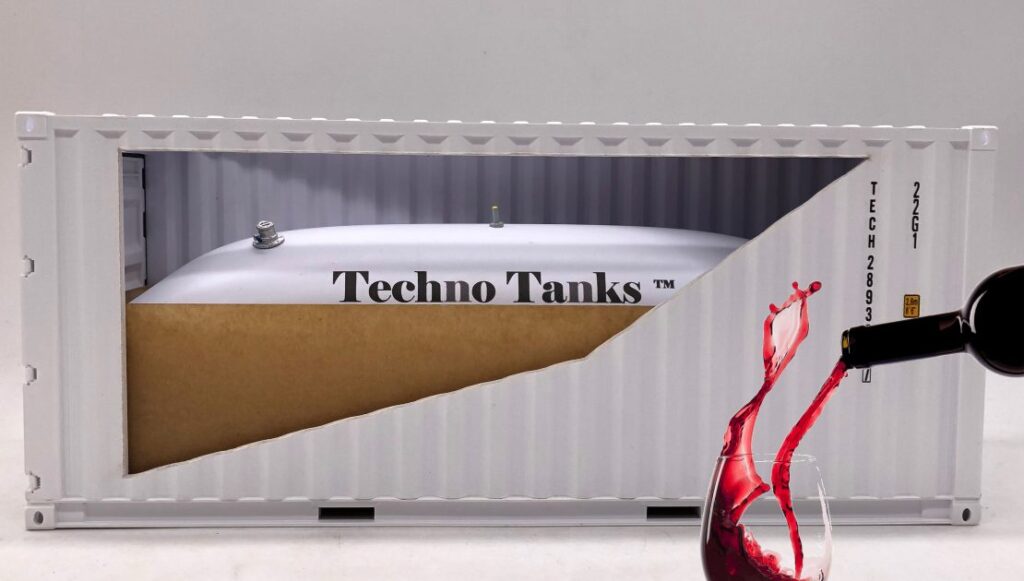

The journey begins in the vineyard or cooperative, where the wine is fermented and aged. Once ready, it’s transferred into large, food-grade containers known as flexitanks, which can hold up to 24,000 litres of wine. They’re designed to safeguard the wine’s quality during transit, ensuring it arrives at the bottling facility in optimal condition, all the while economising on shipping space and costs.

Upon reaching the local bottling facility, the wine undergoes a series of steps, beginning with testing to ascertain quality and consistency. Following this, the wine is filtered and prepared for bottling. Modern facilities utilise automated bottling lines for a series of tasks, from sterilising bottles to corking and labelling.

There are many merits to local bottling. Notably, it diminishes the wine’s carbon footprint by significantly reducing the weight and volume of goods transported, thereby lessening fuel consumption. It also offers a considerable UK economic boost by generating jobs in areas from bulk wine handling and bottling to marketing and retail.

The quality of wine doesn’t necessarily hinge on whether it’s bottled at the vineyard or at a dedicated facility elsewhere. Key considerations revolve around effective oxygen management, filtration, and eliminating hazards like glass or foreign bodies. Dedicated facilities usually have robust procedures and advanced equipment to manage these aspects, such as bottling under CO2 or nitrogen and conducting regular quality checks. Conversely, smaller producers who use their bottling lines infrequently or rely on mobile lines might face challenges with outdated procedures or ineffective equipment. Ultimately, it is attention to detail that matters, rather than the location of bottling.

One aspect to consider is the potential use of dimethyl dicarbonate, also known as Velcorin, as a preservative in wines that are transported in large containers. Its presence is thought to contribute to making these wines more likely to cause headaches.

For companies like Greencroft Bottling, this bulk bottling represents a thriving industry. To facilitate their growth, they’ve recently invested £20 million in a new, renewable-powered facility. Covering more than 22,000 square metres, the building doubles the potential capacity at Greencroft Bottling to 400 million litres annually, equivalent to 28% of all wine sold in the UK.

In conclusion, the practice of bulk packing and local bottling is an economically efficient and environmentally friendly solution within the wine industry.