Wine bottle closures sit at the awkward junction of tradition and engineering. They have to create an airtight seal, survive transport, tolerate temperature swings, open cleanly at the table, and then stay out of the way of the wine’s aroma and flavour for months or decades. At the same time, closures carry powerful cultural meanings. A natural cork can signal tradition and ageworthiness, while a screw cap can signal modernity, convenience, and sometimes, perhaps unfairly, “cheapness”. Understanding closures properly means treating them as a controlled interface between wine and the outside world, where tiny differences in oxygen movement, chemical interaction, and mechanical performance can shape what ends up in the glass.

The central technical job of any closure is to manage gas exchange, especially oxygen. Completely eliminating oxygen is rarely the goal, because wines are bottled with a small amount of dissolved oxygen and headspace oxygen already present and many styles evolve beneficially with very low, steady oxygen ingress over time. The problem is variability and excess. Too much oxygen over months can push wines towards premature oxidation, flattening fruit and accelerating browning, while too little oxygen combined with certain winemaking choices can increase the risk of reductive aromas such as struck flint, rubber, or cabbage-like sulphur notes. Modern closure selection is therefore as much about choosing a predictable oxygen transmission rate as it is about simply “sealing” the bottle.

Natural cork, cut from the bark of cork oak, became dominant because it is elastic, compressible and unusually good at maintaining a seal against glass over long periods. When inserted, cork’s cell structure compresses and then gently expands, creating radial pressure that helps resist leaks. It also performs well with the ritual of opening and the aesthetics of fine wine. Yet natural cork’s greatest weakness is natural variability. Even within a single batch, differences in density and channel structure can change oxygen ingress and the risk of leakage. On top of that, cork can carry compounds that lead to musty taints, the most infamous being those associated with haloanisoles such as TCA, which can mute fruit and give damp cardboard aromas even at extremely low concentrations. The last few decades have seen major improvements in cork processing and quality control, but the risk cannot be driven to absolute zero as long as the raw material comes from nature.

Because of that variability, engineered cork options have grown. Traditional agglomerated corks, made by bonding granulated cork with binders, are commonly used for quicker-turnover wines, and they tend to be more uniform than one-piece natural cork while still offering a familiar look and feel. Micro-agglomerated and “technical” corks go further by tightly controlling granule size, density, and treatment steps to reduce taint risk and narrow the range of oxygen transmission. The trade-off is that these closures can introduce their own considerations, such as the choice of binder, the long-term behaviour of the material under compression, and the way the closure interacts with the wine’s aromatics. Still, for many producers, the appeal is straightforward. Significantly improved consistency from bottle to bottle without abandoning the cork aesthetic.

Screw caps, typically aluminium with an internal liner, solve a different set of problems. Mechanically, they are excellent at preventing leakage and are resilient in transport, while also offering easy opening and resealing. Their performance depends heavily on the liner material, which acts as the true barrier. Some liners allow extremely low oxygen ingress, while others are designed to permit a little more, giving winemakers a way to match closure behaviour to wine style. Screw caps remove cork taint from the equation, but they can shift the balance of bottle ageing. Very low oxygen ingress can be beneficial for preserving primary fruit and freshness, yet it can also make any latent tendency towards reduction more noticeable if the wine chemistry and sulphur dioxide regime are not aligned with the closure. In practice, screw caps often work best when the whole production chain, from pressing and clarification through to bottling oxygen pickup, has been tuned with that low-oxygen environment in mind.

Synthetic stoppers were introduced to mimic cork’s convenience while avoiding cork taint, but their track record is mixed because “synthetic” covers a wide range of polymers and manufacturing approaches. Early versions sometimes suffered from higher oxygen ingress, leading to faster flavour development and, in some cases, earlier oxidation, especially in aromatic whites. Some also had issues with scalping, where certain aroma molecules are absorbed by the polymer, subtly changing the wine’s profile. Mechanical behaviour matters too. Extraction forces can be high, resealing can be unreliable and long-term creep can reduce sealing pressure. Newer synthetic closures can be better engineered, but the category still demands careful matching of material properties to intended shelf life and storage conditions.

Glass stoppers, which seal using a precisely machined glass plug and an inert sealing ring, aim to combine a premium look with neutral flavour impact and reliable resealability. Their appeal is strongest for aromatic styles where neutrality is prized, and for wines intended to be consumed relatively young, where the closure’s clarity and ritual can be a marketing advantage. They do, however, require compatible bottle finishes and careful bottling-line setup to avoid chipping, misalignment, or inconsistent seating. Their oxygen management is largely determined by the sealing ring system, which means performance can be quite consistent when the components are well matched, but, as with any closure, the details of specification matter more than the headline category.

Sparkling wines add another layer because of pressure. During secondary fermentation in bottle, many producers rely on a crown cap with a small plastic cup to trap sediment, because it is cheap, strong, and reliable under pressure. After riddling and disgorgement, the final closure is usually a cork designed for sparkling wine: a dense section at the bottom to seal, with agglomerated material above that forms the familiar mushroom shape once secured under a wire cage. Here, the closure is not only a barrier but also a structural component resisting internal pressure. Oxygen ingress still matters, but so do mechanical safety and the gradual relaxation of materials over time. The design choices in sparkling closures reflect the need to balance seal integrity, ease of disgorgement operations, and the sensory evolution of wines that may spend long periods on lees.

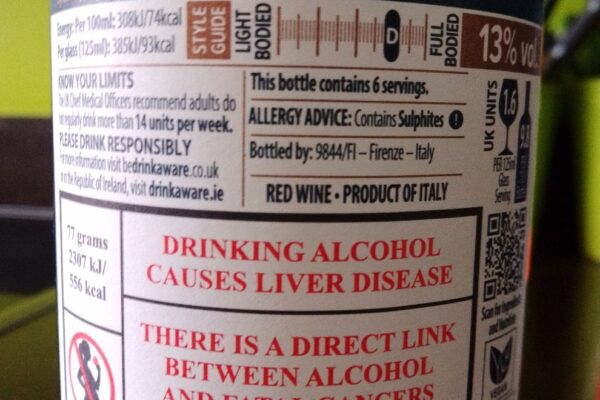

Sustainability has become a major part of the conversation, but it is not as simple as “natural equals green”. Natural cork comes from a renewable bark harvest and is often associated with biodiversity benefits where cork landscapes are maintained, yet it must be transported and processed, and wastage matters. Aluminium screw caps are highly recyclable in many places, but recycling rates depend on local systems and consumer behaviour, and liners introduce mixed materials that complicate processing. Synthetic closures raise questions about fossil-based inputs and end-of-life disposal, though some newer options use plant-derived polymers. Glass stoppers are inert and recyclable as glass, but their production is energy intensive and they may increase transport weight.

Consumer perception remains powerful, but it changes slowly. In some markets, a cork still signals ceremony and prestige, and the pop of a cork is part of the experience producers want to sell. In others, screw caps are widely accepted for premium wines because they deliver consistency and convenience without implying lower quality. The interesting point is that perception can lag behind reality. A well-specified screw cap can protect a fine wine beautifully, while a low-grade natural cork can ruin one.

For drinkers, the most useful thing is that closure type is not a simple quality ranking. It is a set of trade-offs between variability, oxygen management, taint risk, convenience and the intended ageing curve. If you are buying wines to drink young and want freshness, consistency, and easy opening, many modern alternative closures can be excellent. If you are cellaring wines for long ageing, what matters is less the romance of the closure and more the producer’s overall approach and whether the chosen closure specification is known to behave consistently over time.