Champagne, the world’s most celebrated sparkling wine, has captivated connoisseurs for centuries with its effervescence, complexity and prestige.

This sparkling wine has evolved from humble beginnings to become a global symbol of celebration and luxury, with a rich history, distinctive production methods and diverse styles that continue to evolve to meet contemporary challenges and tastes.

The Historical Evolution of Champagne

The story of Champagne begins in the 5th century, possibly earlier, when Romans established vineyards in northeastern France. Initially, the wines produced in this region were still wines, pale, pinkish liquids made primarily from Pinot Noir grapes, bearing little resemblance to the sparkling wine we know today.

The region’s association with prestige began in 987 when Hugh Capet was crowned King of France at Reims Cathedral, initiating a tradition that put local wines on prominent display at coronation banquets. Despite this royal connection, early Champenois winemakers found themselves envious of their southern neighbours in Burgundy, whose red wines enjoyed far greater acclaim.

The northern climate of Champagne presented significant challenges for winemaking. Grapes struggled to ripen fully, resulting in wines with high acidity and low sugar levels that were thinner and lighter-bodied than their Burgundian counterparts. Additionally, cold winter temperatures frequently halted fermentation prematurely in the cellars. When spring arrived, dormant yeast cells would reawaken and restart fermentation, producing carbon dioxide that created pressure within bottled wines.

This phenomenon initially horrified early Champenois winemakers, who considered bubbles a fault rather than a feature. As late as the 17th century, prominent figures such as the Benedictine monk Dom Pérignon (1638-1715) were actively trying to eliminate bubbles from their wines. However, whilst French consumers preferred their Champagne still, British drinkers developed an appreciation for the unique bubbly quality, helping to establish the popularity of sparkling Champagne.

Champagne Region and Growing Districts

The Champagne region is renowned for its distinct growing districts, each contributing unique characteristics to the final blends. It encompasses 34,300 hectares of vineyards spread across five departments and four main wine districts, with 319 villages classified as crus.

- Marne Valley: This region spans 8,000 hectares of vineyards, predominantly producing Champagne “blanc de noirs” from red grape varieties. It holds historical significance as the birthplace of Champagne, where Dom Pérignon developed sparkling wine at Hautvillers during the 17th century.

- Côte des Blancs: Located south of Épernay, it covers 3,300 hectares across 20 kilometres and includes twelve villages, six of which are classified as Grand Cru. The region benefits from a unique microclimate and limestone soil ideal for cultivating Chardonnay, imparting mineral qualities to the grapes.

- Côte des Bar: Situated in the Aube department, this area forms an arc south of Troyes and extends 70 kilometres. It features diverse soils (marl, limestone, clay) and comprises 62 villages. Les Riceys is particularly notable for its 800 hectares producing wines under three appellations: Champagne, Coteaux Champenois, and Rosé des Riceys.

The Champagne region is home to about 2,124 Champagne houses and approximately 19,000 growers, showcasing its vast scale and diversity in production. These houses and growers collectively produce around 300 million bottles annually, contributing to the complex blends that define Champagne.

The Champagne-Making Process

The production of Champagne, whether vintage or non-vintage, follows the traditional method, known as Méthode Traditionelle or Méthode Champenoise. This intricate process involves two fermentations and meticulous attention to detail, but there are distinct differences in the winemaking and ageing requirements for vintage and non-vintage Champagnes.

For vintage Champagne, only grapes harvested in a single exceptional year are used, reflecting the unique characteristics of that year’s terroir and climate. These wines are produced only in years deemed of sufficiently high quality. After the first fermentation, which transforms grape juice into still wine, no blending with reserve wines from other years occurs. The wine undergoes a second fermentation in the bottle, followed by a minimum of three years of ageing on the lees (dead yeast cells), although many houses extend this period significantly to enhance complexity. This prolonged ageing develops rich autolytic notes such as brioche, toasted nuts, and honey. Vintage Champagnes often continue to evolve for decades in the bottle, gaining tertiary flavours like dried fruit and earthy tones over time.

Non-vintage Champagne, by contrast, is made from a blend of base wines from multiple years. This blending process ensures consistency in flavour and maintains a house’s signature style despite annual variations in weather. After blending, the wine undergoes the same second fermentation in the bottle as vintage Champagne but is required to age for a minimum of 15 months before release, with at least 12 months spent on the lees. In practice, many non-vintage Champagnes are aged for 2–3 years to achieve greater balance and complexity. The shorter ageing period compared to vintage Champagne results in fresher fruit flavours with lighter autolytic notes such as subtle hints of bread or nuts.

Appellation and Protection of the Champagne Name

The Champagne designation represents one of the most fiercely protected appellations in the world of wine. Officially recognised as an Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) on 29 June 1936, the legal protection of the Champagne name actually dates back much further, reflecting the producers’ commitment to preserving their unique heritage.

As early as the mid-19th century, Champagne makers began organising collective efforts to defend their product against imitations and misuse by other sparkling wine producers who sought to capitalise unfairly on Champagne’s prestigious reputation. This protection became more formalised with the establishment of the Comité interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne (CIVC) in 1941, an organisation dedicated to safeguarding the Champagne designation globally.

Initially, the CIVC primarily targeted sparkling wines that used the Champagne name despite originating outside the legally defined geographical area. Over time, their protective measures expanded to ensure that even authentic Champagne producers adhered to the strict production process required by the designation. This two-pronged approach guarantees consumers that wines bearing the Champagne name meet the exacting standards that justify its reputation for excellence.

In the mid-1980s, recognising the growing prestige associated with the name “Champagne,” the Comité Champagne intensified its lobbying efforts to strengthen protection further. These initiatives resulted in regulations prohibiting any unfair use that attempts to trade on Champagne’s reputation or image, even outside the wine industry.

Through persistent advocacy, the Champagne designation now enjoys recognition and protection in more than 130 countries, ensuring that the term “Champagne” represents not merely a style of sparkling wine but a product with specific geographical origins and production methods.

Grapes and the Art of Blending

The art of blending, or “assemblage”, stands as the defining feature of Champagne production, comparable to a Michelin-starred chef creating a signature dish. This process involves skilfully combining clear wines from different vineyards, grape varieties, and vintages, each with distinctive characteristics, to achieve complexity and balance in the final product.

Three primary grape varieties form the foundation of Champagne blending: Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier. Chardonnay, covering approximately 30% of the Champagne region’s vineyard area, contributes elegance, finesse, and longevity. Pinot Noir, accounting for 38% of plantings, provides structure, body, and depth. Pinot Meunier, representing 31% of vineyards, adds fruitiness, roundness, and early approachability to the blend.

The Chef de Cave (Cellar Master) orchestrates this blending process with meticulous attention to detail, evaluating hundreds of base wines to create a harmonious final product. For example, rosé Champagne blending demands a delicate balance, typically combining Chardonnay for finesse with Pinot Noir for fruit and colour. These precise combinations become the signature of each Champagne house, maintained consistently year after year despite natural variations in grape quality and characteristics.

The uniqueness of these three grape varieties enables winemakers to create blended Champagnes characterised by complementary flavours and distinctive contrasts. Some blends emphasise the freshness and minerality of Chardonnay, whilst others showcase the richness and power of Pinot Noir, or the accessibility and fruit-forward nature of Pinot Meunier. This diversity in blending approaches helps explain the wide range of styles available in the Champagne market.

Styles of Champagne

The world of Champagne encompasses a remarkable diversity of styles, ranging from rich, decadent, and full-bodied expressions to rapier-fresh, saline versions, with countless variations between these extremes. This variety ensures that virtually every palate can find a Champagne to enjoy.

Non-vintage Champagne, created by blending wines from multiple years, represents the foundation of most producers’ offerings. These wines express the consistent house style that producers maintain year after year. Vintage Champagne, produced only in exceptional years using grapes from a single harvest, typically shows greater complexity and aging potential, reflecting the unique character of that particular growing season.

Other significant styles include blanc de blancs, made exclusively from white grapes (primarily Chardonnay), prized for their elegance, finesse, and mineral qualities. Conversely, Blanc de Noirs utilises only red grapes (Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier), resulting in fuller-bodied wines with greater richness and structure. Rosé Champagne, whether created through limited red grape skin contact or by adding a small amount of still red wine to the blend, offers appealing berry flavours and visual charm.

Perhaps the most significant stylistic development in recent decades has been the rise of grower Champagnes, produced by the estates that own the vineyards where the grapes are grown. These terroir-focused wines, identified by “RM” (Récoltant-Manipulant) on the label, contrast with the consistent house styles of larger producers by expressing the distinctive characteristics of specific vineyards or villages.

The sweetness of sparkling wine is influenced by the dosage, a mixture of sugar and wine added after disgorgement to balance acidity and refine the final flavour profile. This dosage plays a crucial role in defining the wine’s style, ranging from the driest options, such as Brut Nature and Extra Brut, which contain no to little added sugar, to progressively sweeter categories like Brut, Extra Dry, Sec, Demi-Sec, and Doux. Each level of sweetness contributes to distinct taste characteristics, catering to different palates and occasions.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable shift in consumer preferences towards drier styles of sparkling wine. This trend has prompted many producers to reduce the dosage levels in their wines, aiming to highlight the purity and complexity of the wine itself rather than masking its natural qualities with excessive sweetness. By lowering the sugar content, winemakers can better showcase the nuances of terroir, grape variety, and craftsmanship, allowing the intrinsic attributes of the wine to take centre stage.

Champagne Houses and Their Distinctive Styles

The grand Champagne houses, with their consistent house styles maintained across decades or even centuries, have defined the region’s global reputation. These larger producers, such as Mumm, Moët et Chandon, and Veuve Clicquot, may source grapes from as many as 80 different vineyards throughout Champagne to achieve their distinctive signatures.

Boizel, a medium-sized family-run house in Epernay, exemplifies a classic refined style that prioritises elegance over weight. Relying on quality sources of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, their champagnes serve perfectly as aperitifs and have earned distinction as the house champagne at Glyndebourne.

In striking contrast, Bollinger produces champagnes dominated by Pinot Noir, creating full-bodied, rich, and immensely complex wines. Their distinctive character derives from exceptional reserve wines, some stored in magnum-sized bottles for up to ten years. With extensive vineyard holdings, particularly in the prestigious Pinot Noir areas around Aÿ, Bollinger approaches self-sufficiency in grape sourcing.

Alfred Gratien crafts a unique style dominated by Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier from outstanding vineyard sites. Their distinctive approach includes fermenting all components of The Society’s Champagne in small oak barrels, with approximately 900 barrels stored for evaluation before the blending process begins each new year.

Other notable houses include Laurent-Perrier, known for elegant, complex champagnes with a lighter profile; Louis Roederer, producing rich, full-bodied, creamy wines once favoured by the Russian Tsar; Pol Roger, whose balanced approach using equal parts of all three grape varieties has made the UK its largest market and won the favour of Sir Winston Churchill; and Taittinger, renowned for elegance and refinement despite emphasising Pinot in their blends.

Each house carefully maintains its distinctive approach across generations, creating recognisable styles that loyal consumers can depend upon year after year.

Grower Champagne: The Rise of Artisanal Producers

While large Champagne houses have historically dominated the market, recent decades have witnessed the emergence of Grower Champagnes as a significant and influential category. Also known as Artisan Champagnes, these wines are produced by estates that own the vineyards where their grapes are grown, identified by the designation “RM” (Récoltant-Manipulant) on the label.

The philosophy behind Grower Champagne differs fundamentally from that of larger houses. Rather than creating a consistent style by blending wines from numerous vineyards across the region, growers typically focus on expressing the unique characteristics of specific terroirs, often a single vineyard or vineyards clustered around a particular village. This approach has been described as “artisanal winemaking” with terroir at the forefront, allowing each wine to reflect the distinctive qualities of its origin and the particular conditions of each vintage.

The scale of grower operations is remarkable: over 19,000 independent growers manage nearly 88% of Champagne’s vineyard land, with approximately 5,000 producing wine from their own grapes. Despite this prevalence in production, Grower Champagnes remain relatively uncommon in export markets, in 2014, they constituted only 5% of Champagne imported into the United States.

Grower Champagnes typically reach the market at a younger age than those from larger houses, partly due to the more limited financial resources available for extended aging and storage. Many also feature lower dosage levels, sometimes none at all, compared to négociant manipulant bottlings, reflecting a growing preference for drier styles that showcase the inherent qualities of the base wines.

Notable producers in this category include Nomine-Renard, Harlin Père & Fils, Franck Bonville, Roger Coulon, Collard-Picard, Egly-Ouriet, Tarlant, and Chartogne-Taillet, each offering distinctive expressions of their particular terroirs.

Export Markets and UK Consumption

The United Kingdom has historically maintained a special relationship with Champagne, dating back to the early development of the sparkling style. British consumers developed an appreciation for bubbly Champagne before French drinkers, who initially preferred their local wine in a still format. This early affinity has evolved into a enduring market connection, with the UK representing a significant export destination for numerous Champagne producers.

For some houses, such as Pol Roger, the UK constitutes their largest market, reflecting British consumers’ sophisticated appreciation for classic Champagne styles. The long-standing relationship between Britain and Champagne extends beyond mere consumption to cultural associations, with Champagne featuring prominently in British celebrations, sporting events, and social occasions.

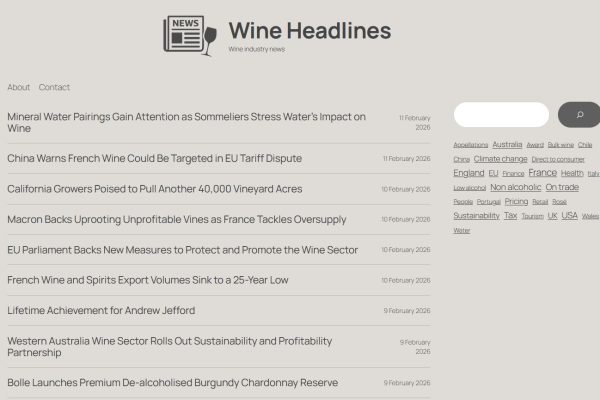

In 2024, the United Kingdom imported 22.3 million bottles of Champagne, a decline of 12.7% compared to the previous year. This figure reflects a drop of nearly three million bottles and brings the UK market back to a size last seen in 1997. Despite this reduction, the UK remains the second-largest export market for Champagne globally, following the United States. The total value of these imports amounted to €518.7 million, representing a 5.7% decrease from 2023.

The decline in shipments was influenced by several factors, including excess stock from lower-than-expected festive sales in late 2023, rising prices (with Champagne becoming 25% more expensive over three years), and increased competition from other alcoholic beverages like cocktails and alternative sparkling wines. Broader economic and political challenges also contributed to reduced demand.

Modern Innovations and Trends

The Champagne industry, whilst deeply rooted in tradition, continues to evolve through various innovations and shifting consumer preferences. One of the most significant trends has been the rise of Grower Champagnes, which offer more terroir-specific expressions compared to the consistent house styles of larger producers. This movement reflects broader consumer interest in authenticity, provenance, and artisanal production methods across the food and beverage sector.

Another notable trend involves dosage levels, with many producers reducing the amount of sugar added after disgorgement to create drier styles. Grower Champagnes often feature lower dosage than those from larger houses, responding to evolving consumer preferences for wines that more clearly express their fundamental character without the masking effect of sweetness.

Future Challenges for Champagne

The Champagne industry faces numerous challenges that will shape its future development. Climate change presents perhaps the most significant long-term concern, potentially altering growing conditions in a region already at the northern limits of viable viticulture. Rising temperatures may affect the characteristic high acidity that gives Champagne its structure and aging potential, whilst changing rainfall patterns and increased extreme weather events could disrupt the delicate balance of grape development.

Protecting the Champagne designation remains an ongoing challenge, requiring vigilant defence against misuse of the name by producers outside the region. Despite recognition in over 130 countries, the Comité Champagne must continuously monitor and enforce protection to preserve the value and reputation of authentic Champagne.

Market challenges include adapting to evolving consumer preferences, particularly among younger generations with different purchasing patterns and occasion-driven consumption. Additionally, competition from other sparkling wines, including Prosecco, Cava, and English sparkling wine, continues to intensify in key markets.

The future of Champagne lies in navigating environmental challenges whilst continuing to innovate within the constraints of tradition. Whether produced by historic houses maintaining consistent styles across generations or by growers expressing the distinctive character of individual vineyards, Champagne remains unmatched in its combination of complexity, prestige and celebratory associations.